"It's too early to tell."

The Economist, Special Holiday Double Issue, December 17 2011:

Nicholas Taleb:

"....journalism may be the greatest plague we face today- as the world becomes more and more complicated and our minds are trained for more and more simplification...

...To be competent, a journalist should view matters like a historian, and play down the value of information he is providing…Not only is it difficult for the journalist to think more like a historian, but it is, alas, the historian who is becoming more like the journalist.”

Francis Fukuyama, WSJ, June 28 2013:

"The new middle class is not just a challenge for authoritarian regimes or new democracies. No established democracy should believe it can rest on its laurels, simply because it holds elections and has leaders who do well in opinion polls. The technologically empowered middle class will be highly demanding of their politicians across the board"

This refers to the leader in Marathi daily Loksatta (लोकसत्ता) on July 4 2013. If you read Marathi, read it here.

I read it twice to make some sense out of it. I could not.

My confusion first started with the word used in the title: 'रिअॅक्शनरावांचा राडा' (Mess of Messrs Reactions)

I did not know there was a word like 'रिअॅक्शनराव' (Reaction-rao) in English/ Marathi. Was it 'रिअॅक्शनीराव' (Reactionary-rao)? When I saw the web address, it reads "mess of reactionaries". So it indeed was 'रिअॅक्शनरीरावांचा राडा'!.

I feel there is a lot of difference between 'रिअॅक्शनराव' (Messrs Reactions) and 'रिअॅक्शनरीराव' (Messrs Reactionaries). The former would refer to the people who react and the latter to the people who are reactionary.

( Btw- I also wonder why Marathi word for reactionary- प्रतिगामी- not used. If it were, it would read 'प्रतिगामीरावांचा राडा')

Let me now turn to the contents of the piece. It confused me more even after replacing 'reactions' with 'reactionaries'.

The leader starts with :

"राजकीय व्यवस्थेत सामील न होता तिच्याविषयी घृणा बाळगत ट्विटर, फेसबुक आदी माध्यमांव्दारे बदलाची अपेक्षा ठेवणारा वर्ग ठोस पर्यायही देत नाही हे धोकादायक आहे. व्यवस्थेचा फायदा घेत ती झीडकारण्याची भाषा करणाऱ्या रिअॅक्शनरावांना कोणतेही राजकीय अधिष्ठान नाही हेच जगभरातील अलीकडच्या उठावांचे समान सूत्र आहे."

(It's dangerous that a class, without offering a solid alternative, expects a change in the political system it hates without participating in it, using media such as Twitter and Facebook. The recent uprisings across the world have the same thread: 'Messrs Reactionaries' who while exploiting the system use the language of discarding it have no political base.)

Is it an attack on the mostly middle-class people who think they can usher in a revolution or an alternative system using tools like Twitter and Facebook? Is it also an attack on recent uprisings and such movements? Does the newspaper imply that 'reactionaries' use social media to instigate not-fully-thought-through uprisings against the establishment?

Reactionary is by a definition 'an extreme conservative; an opponent of progress or liberalism'.

Therefore, you can call these people- who either take part in such uprisings or accompanying social media movements- anything but reactionaries!

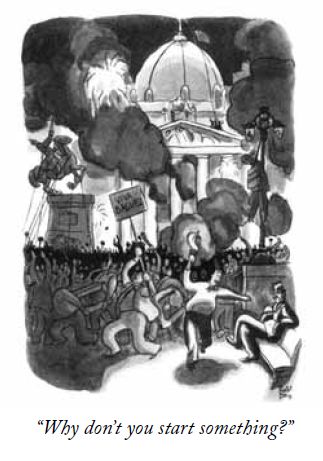

On the contrary, these people are progressivists (those who favor progress toward better conditions in government and society)! Some of them may be extremely naive even arrogant but they aren't reactionaries and some may just be responding to their wife's- I assume- nagging- "Why don't you start something?"- as in the picture below.

Artist: Robert J Day, The New Yorker, July 16 1932

As The Economist quote at the top says, there is nothing new about social media. We always had social media and also the smart people to leverage it to precipitate a revolution. Therefore, why blame 'new' social media?

In any case, as Chris Lehmann explains below, they only played a marginal role in Egypt in 2011?

"But there is a final lesson from ancient Egyptian history that those urging regime change should heed. Today, tanks stand guard beside the Pyramids of Giza, the grandest symbols of authoritarian rule ever built. The pyramids sum up the unbridled confidence of ancient Egypt at the height of its power. The pyramid-builders must have assumed that the glories of pharaonic civilization would last forever. What brought the Age of the Pyramid to an end in 2175 B.C. was not war, invasion, or pestilence, but a political vacuum following the demise of a long-lived ruler. Factionalism and paralysis beset the Egyptian government, the economy collapsed and the country was plunged into a protracted civil war.

Egyptian history has a depressing habit of repeating itself. Let us all hope that, in this last respect, it does not."

If you accused Mr. Wilkinson of being a reactionary in 2011, you may now laud him as a visionary!

Does Loksatta expect people who start or instigate uprisings to fully think through their consequences and only after suggesting a solid alternative to the existing order? Has recorded history worked like that?

The late Jacques Barzun wrote in "From Dawn to Decadence: 1500 to the Present- 500 Years of Western Cultural Life", 2000:

"How a revolution erupts from a commonplace event—tidal wave from a ripple—is cause for endless astonishment. Neither Luther in 1517 nor the men who gathered at Versailles in 1789 intended at first what they produced at last. Even less did the Russian Liberals who made the revolution of 1917 foresee what followed. All were as ignorant as everybody else of how much was about to be destroyed. Nor could they guess what feverish feelings, what strange behavior ensue when revolution, great or short-lived, is in the air...

...A curious leveling takes place: the common people learn words and ideas hitherto not familiar and not interesting and discuss them like intellectuals, while others neglect their usual concerns—art, philosophy, scholarship—because there is only one compelling topic, the revolutionary Idea. The welltodo and the "right-thinking," full of fear, come together to defend their possessions and habits. But counsels are divided and many see their young "taking the wrong side." The powers that be wonder and keep watch, with fleeting thoughts of advantage to be had from the confusion. Leaders of opinion try to put together some of the ideas

afloat into a position which they mean to fight for. They will reassure others, or preach boldness, and anyhow head the movement. Voices grow shrill, parties form and adopt names or are tagged with them in derision and contempt. Again and again comes the shock of broken friendships, broken families. As time goes on, "betraying the cause" is an incessant charge, and there are indeed turncoats. Authorities are bewildered,

heads of institutions try threats and concessions by turns, hoping the surge of subversion will collapse like previous ones. But none of this holds back that transfer of power and property which is the mark of revolution and which in the end establishes the Idea."

courtesy: Wikipedia

2 comments:

Aniruddha,

--- Zhou Enlai (1898-1976), the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, on the success of the 1789 French Revolution:

"It's too early to tell." ---

I completely agree. We can only debate, but it is always too early to pass a concluding remark. But journalists seem to be obsessed with that.

Nicholas Taleb:

"....journalism may be the greatest plague we face today- as the world becomes more and more complicated and our minds are trained for more and more simplification".

“To be competent, a journalist should view matters like a historian, and play down the value of information he is providing…Not only is it difficult for the journalist to think more like a historian, but it is, alas, the historian who is becoming more like the journalist.”

Post a Comment